Decisions Decisions

Making decisions is difficult.

I'm sure there are people out there who can just look at a bunch of options, pick one, and then move on with their lives without a second thought.

Not me though.

Decisions require consideration; they require an understanding of the options, a comparison of the trade-offs and clear communication of the selected path forward.

In an asynchronous workplace, that last part is particularly important, so that's what this blog post is going to focus on.

What's Your Name?

The first model for communicating decisions is the Lightweight Decision Register (LDR).

An LDR is not interactive. It's not intended to help facilitate making the decision.

It is a quick summary of a decision that has already been made, documented clearly in some sort of easily accessible manner, like a Confluence page.

An LDR explains what the decision is, why the decision was made, any competing options that were considered and any follow-up actions necessary.

It does all of these things in a very concise manner, focusing the majority of its efforts on what needs to happen now that the decision has been made. The important thing is that the ramifications of the decision are communicated.

I don't generally make use of LDR's very much.

People like to be considered when there are decisions to be made and it can feel like a bit of a dick move to just write about the decision afterwards, especially if not everyone was included in the conversation that led to it.

Obviously, it's still better than not recording the decision at all, but if I need to make a decision and I think the ramifications are going to affect a bunch of people, I'll try a little bit harder and use one of the other models below.

Speaking of which.

What's The Last Thing You Remember?

The second model is the Request for Comments (RFC).

An RFC is a complete proposal, explaining in detail a potential solution to a problem or a way to exploit an opportunity. It is opinionated, in that it focuses on explaining a recommended path forward, though in the interests of fleshing out the situation, it may mention other options that were considered.

In comparison to an LDR, an RFC is interactive. By getting input from interested and affected stakeholders in the form of comments, the person driving the RFC can adjust and adapt their proposal in order to make a better decision about how to move forward.

After the decision has been made, the RFC stands as a record of the decision, in basically exactly the same way as an LDR does, except with more information and having had more involvement from stakeholders.

I use RFC's a lot.

Typically, if there is a problem I'm trying to solve or an opportunity I want to exploit, I have a pretty good idea of what path I want to follow.

What I don't have is alternative perspectives, so putting together an RFC that explains what I want to happen and using that as a mechanism to engage with people helps to create a better outcome.

It stops me from getting fixated on the idea I had in my head and it helps other people to come to terms with whatever change the RFC might be proposing, well in advance of actually executing it.

Don't underestimate that last point; one of the hardest things about decisions is actually pushing forward with the resulting actions. The sooner you get people thinking about what is going to change, the easier it will be for them to digest said changes and the easier it will be to make those changes.

Why Are You Here?

The third and final model is the DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributors, Informed).

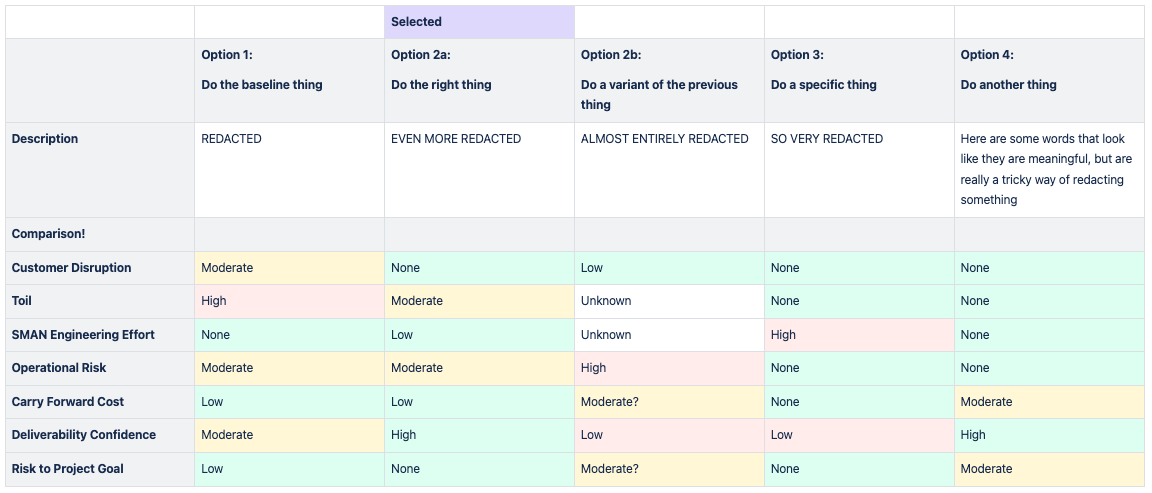

A DACI is a full-fledged, collaborative, decision making process. It explains in detail the potential solutions to a problem or ways to exploit an opportunity. That's solutions plural, because the intent of a DACI is to engage with interested stakeholders around the available options and to then select one in order to move forward.

As you can probably imagine, a DACI is a lot more heavyweight than an RFC or LDR, not only requiring significantly more effort to explore and document the options, but also to contrast and compare them against one another.

In fact, that's probably the most important difference between a DACI and an RFC; the comparison of the options.

My preferred approach is to use a table, with the options represented as columns and the rows representing the dimensions, colour coding as appropriate to represent the strengths and weaknesses of each option in comparison to the others.

I use DACI's sparingly, mostly because of the higher cost in creating them. It takes a meaningful amount of effort to come up with options and to them explore those options enough in order to be able to compare them.

DACI's also tend to be a bit more difficult to push through to a conclusion, as people quibble over the intricacies of the various options. That's something that can be mitigated by an appropriately motivated driver and a clear approver, but again, it takes extra effort.

The benefit you get for that effort is a clearer understanding of the trade-offs that you're making by selecting a particular option, along with potentially more buy-in from those who collaborated on making the decision (because they can see that you have considered all of the angles).

I Want To Play A Game

All of the models described above (LDR, RFC, DACI) follow a consistent structural pattern.

First, you want to include some background information and context to set the scene, along with any supporting data.

Depending on the model you're following, you then either explain the path forward briefly (an LDR), in detail (an RFC) or you describe and compare all potential options (a DACI).

After that, you include supplementary information as necessary. This is most often useful in the case of a DACI, as you want the representation of the options to be easy to comprehend in a single glance, so providing a high-level view in the table and then delving into the detail afterwards is a good way to present things.

Finally comes actions, things that need to happen post the decision being made. This section is useful in the future when you need to go back and review a decision and check to see if the appropriate measures were taken after the fact. This is also a useful place to summarise what the decision actually was, though it's best to echo that at the top of the document as well.

I often include a notes section below this point, to keep a record of conversations or meaningful changes during the process of driving the decision, but that's just me. If you do this, make sure you de-emphasise it to ensure that the rest of the document gets the majority of the reader's attention.

Game Over

LDRs, RFCs and DACIs are all useful ways to communicate and collaborate on decisions, but they really shine in asynchronous environments. That's probably why I find them so useful, because that is my life.

As always, choose the model based on your need and don't be afraid to switch from one to another as your understanding of the situation grows.

Finally, don't feel like you have to always use them. Sometimes a decision is easy and all of the people who need to know about it are right there, so there is no need to go to the effort of writing it down.

Of course, then you'd miss out on the pleasure of writing, and I don't know why you'd do that to yourself.

Member discussion